Article at a glance

- An increasing number of policy and governance challenges such as inclusive growth, poverty reduction, government accountability, business integrity, and innovation demand private sector participation in order to generate viable solutions.

- Public-private dialogue (PPD) provides a structured, participatory, and inclusive approach to policymaking directed at reforming governance and the business climate, especially where other policy institutions are underperforming. Governments that listen to the private sector are more likely to design credible reforms and win support for their policies.

- Dialogue platforms have proven their ability to deliver results. Practitioners around the world can learn from and apply successful PPD approaches through a new community of practice online hub, www.publicprivatedialogue.org.

Introduction

An increasing number of policy and governance challenges around the world demand private sector participation in order to generate viable solutions. Such challenges include inclusive growth, poverty reduction, government accountability, business integrity, national competitiveness, innovation, and access to opportunity. A top recommendation to emerge from the 4th High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness in Busan, Korea, was to embrace “inclusive dialogue for building a policy environment conducive to sustainable development.”1 Subsequently, the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation proposed publicprivate dialogue as a lead indicator of private sector contributions to development.2

More than an idea, structured dialogue mechanisms have been set up in every part of the world and interest has never been greater. A March 2014 International Workshop on Public- Private Dialogue in Frankfurt, Germany, attracted 145 practitioners from 40 countries representing 33 public-private dialogue initiatives.3 Although the obstacles to dialogue can be high, the value of dialogue is now widely recognized by governments and business leaders alike.

The World Bank Group (WBG) and the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) are among the leading international organizations that facilitate and strengthen public-private dialogue around the world as a means to catalyze reforms and promote inclusive policymaking. This joint article outlines the value and application of public-private dialogue in today’s environment and shares effective practices based on WBG’s and CIPE’s experience.

What is Public-Private Dialogue?

Public-private dialogue (PPD) is a structured, participatory, and inclusive approach to policymaking. It is directed at reforming governance and the business climate, especially where other policy institutions are underperforming. Dialogue improves the flow of information relating to economic policy and builds legitimacy into the policy process. It also seeks to overcome impediments to transparency and accommodate greater inclusion of stakeholders in decision-making.

Simply put, dialogue expands the space for policy discovery. Through dialogue, policymakers, constituents, and experts can much more accurately determine the sweet spot for reforms that will satisfy the conditions of policy desirability and political and administrative feasibility. PPDs enable stakeholders to work cooperatively to address state and market collective action problems. They bring together a wide variety of actors such as the private sector, government, civil society, academia, and others who share common interests or concerns surrounding specific policy questions.

PPD is used to set policy priorities, improve legislative proposals, and incorporate feedback into regulatory implementation. It can generate insights, validate policy proposals, or build momentum for change. Dialogue helps reveal to governments the likely micro-economic foundations for growth, but also creates a sense of ownership of reform programs among the business community, which makes policies more likely to succeed in practice.

Benefits of Public-Private Dialogue

Public-private dialogue creates a foundation for market-friendly policies that deepen economic reform and enhance national competitiveness. It has many applications, but is typically geared toward improving the investment climate, removing constraints to development, or formulating industries-specific policies.

Governments that listen to the private sector are more likely to design credible reforms and win support for their policies. They further diversify their sources of information and promote evidence-based policy. Business, for its part, seeks government’s assistance in establishing a lowcost, predictable business environment. Talking together on a regular basis helps build trust and understanding between the sectors.

From the viewpoint of democratic and open governance, a vibrant private contribution to dialogue expands participation in policymaking, improves the quality of business representation, and supplements the performance of democratic institutions. What is more, PPDs build transparency and accountability into policymaking and policy implementation, thereby holding to account both private and public sector stakeholders.

Structured, transparent private sector engagement is a force to counter policymaking that occurs through back-room deals involving a select few. The loudest voices rarely speak in the best interests of private sector growth as a whole, or have broad-based development goals in mind. By contrast, multi-stakeholder platforms shed light on the workings and performance of government institutions and build legitimacy for collaborative decision-making.

Finally, public-private dialogue platforms have proven their ability to deliver results. One evaluation conducted in 2009 of 30 PPDs found that more than 400 reforms had taken place in over 50 areas, producing about $400 million in private sector savings.4 Examples of policy impacts are described in short case studies below.

With Dialogue

|

Without Dialogue

|

Experiences of Public-Private Dialogue

PPDs can address issues at local, national, or international levels, or be organized by industry sector, cluster, or value chain. They can also be time-bound (established to solve a particular set of issues) or institutionalized for in-depth transformation and development.

Dialogue driven by government may take the form of consultation. The process serves the government’s need for information and opens a channel for the expression of private opinions. The private sector also can take initiative in the policy process. By adopting an advocacy approach, it can define the issues, organize itself, and voice its priority needs. Advocacy – a proactive effort to influence policy – makes business an effective contributor to dialogue.

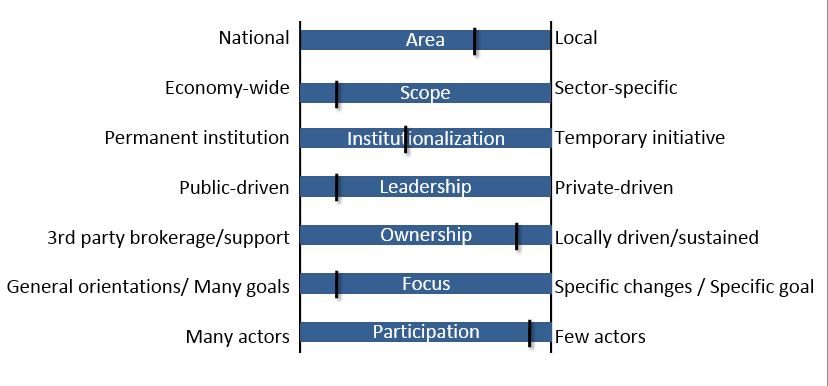

The following 7-point framework demonstrates the different characteristics of a given partnership.5

The cursor for any PPD would indicate: What is the area of the PPD? Is it national or local? What is the scope of the initiative? Is it sector-specific, economy-wide, or topic-wide? What is the level of institutionalization of this initiative? Who are its leaders? Is this initiative driven by the private sector or driven by the government? Who owns it? Is it something locally driven, sustained by the actors themselves, or is it something that is sponsored by third parties such as donors with a lot of support? What is the focus of the partnership? Is the focus to accomplish a few specific changes, with specific goals, or is it to give general orientation for the economy? Who participates actively, and what is the complexity and number of groups involved?

Because of their collaborative development benefits, several international partners have been brokering such dialogue platforms for over a decade. For instance, the World Bank Group has supported for the past 10 years a variety of PPD initiatives in more than 50 countries, including competitiveness partnerships, investors’ advisory councils, presidential investors’ round tables, business forums, and other types of PPD. CIPE for the last 30 years has mobilized representative business associations around the world and strengthened their capacity to advocate for market-oriented policy solutions. The following examples illustrate the diversity of forms which dialogue initiatives have taken, and their ability to drive different types of reform.

Dialogue on the investment climate (Cambodia)

A core motivation for many dialogue initiatives has been to accelerate reforms to the investment climate and improve the enabling environment for business. These initiatives bring public and private sector partners together to diagnose constraints to business, implement policy changes, and thereby increase national competitiveness. This approach is exemplified by Cambodia’s Government-Private Sector Forum, which has convened since 2001 under the chairmanship of the prime minister. The forum was organized around eight sector-specific working groups, each co-chaired by a representative of the private and public sector. Working groups elaborate reforms, and every six months to a year a large and publicized session chaired by the prime minister enacts the changes and/or resolves conflicts. Since the forum’s creation, 16 such plenary sessions have taken place and been televised and broadcast nationwide.

Reforms implemented through Cambodia’s forum generated in excess of $69.2M estimated impact in terms of cost savings to the private sector.6 Some of the more tangible reforms include a reduction in entry fees for Sihanoukville port, a garment sector tax holiday, a reduction from 10 percent to 3 percent for excise tax on landline phone calls, and a reduction in the solvency ratio from 20 to 15 percent for commercial and specialized banks. Moreover, the forum improved government understanding of the private sector’s needs and encouraged the business community to adopt a more holistic view toward improving the economy.7

Sector-specific dialogue (various countries)

In many instances, it makes sense for a PPD to arise between a particular industry, cluster, or value chain in the private sector and those in government responsible for regulating that area of the economy. These sector-specific (or issue-specific) PPDs provide more focus, greater incentives to collaborate, and more opportunity for action. As such, sector-specific strategies are a form of industrial policy. However, unlike many industrial policy strategies in the past that have performed poorly (e.g., misallocating industries, targeting the “wrong” sector), a PPD framework can overcome many of these shortcomings. In particular, PPDs that emphasize local ownership and leadership, promote participatory workshops open to all interested parties (i.e., outreach), encourage firms to cooperate to resolve common problems, and leverage international benchmarking and technical training (potentially provided or funded by donors) can foster transparency, inclusion, and better means to identify areas for sector development.

For some countries, the introduction of PPDs has transformed industries. For example, until a PPD process was introduced in Egypt in 1998, citrus exports only grew to the extent that more irrigated harvest areas were added to the existing arable land. Once the Horticultural Export Improvement Association (HEIA) was introduced, the joint publicprivate engagement efforts took full advantage of the existing land. As a result, Egyptian citrus sector exports grew five-fold in volume and 14-fold in value between 2000 and 2008. A similar pattern can be observed in other Mediterranean countries.8 In the cruise tourism sector, a PPD organized by the Izmir Chamber of Commerce in Turkey contributed to a 100-fold increase in cruise passengers visiting Izmir, from roughly 3,500 passengers in 2003 to 350,000 in 2010. At the local level, PPDs in 10 Spanish regions have increased the competitiveness and output of the citrus sector. The public-private partnership, Barcelona22, has helped the city’s cruise tourism sector (and related industries, such as restaurants, hotels, etc.). Barcelona22 has attracted more than 1,500 companies and created close to 45,000 jobs.

The relevance of PPD to resource-scarce sectors can be illustrated, for example through the Jordan Valley Water Forum (JVWF), which was established in 2011 to address crucial water issues and develop an integrated water management system for the Jordan Valley. The forum promotes collective action by farmers to prepare realistic proposals; review by the public sector of the proposals; and transparent, inclusive discussions among public and private sector stakeholders to determine priority solutions to water sector issues.9 The forum has replaced informal, ad hoc engagement with a coordinated process, which has received the support of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Jordan Valley Authority. The process has resulted in several concrete steps toward rectifying the water crisis, which include: i) breaking the monopoly of the Amman municipal market, ii) providing insurance funds, iii) securing airfreight space in airlines for export of fresh products, and iv) addressing infrastructure maintenance issues along King Abdullah Canal.

Dialogue led by business (Moldova)

The private sector can take initiative in dialogue by adopting an advocacy approach. Developing a national business agenda (NBA) is one way to identify reform priorities and mobilize the business community. Moldova’s National Business Agenda Network, comprised of more than 30 business associations and chambers of commerce, positioned itself as a key stakeholder in policymaking. The Institute for Development and Social Initiatives (IDSI) established four working groups on agribusiness, transportation, construction, and information technology, and hosted an annual business agenda conference attended by government officials, think tanks, business representatives, and the media.

Noteworthy results from the dialogue occurred in the areas of tax collection, state inspections, and customs administration. Legislative changes included the elimination of ad-hoc inspections, and a reduction in the duration of inspections from two months to five days. The government established a one-stop shop for receiving tax reports and providing taxpayer services. In 2013, the Ministry of Economy asked IDSI and the network to sign a Memorandum of Understanding to undertake an independent assessment of the government’s economic reform initiatives.10

Dialogue for small and medium enterprise (Senegal)11

The small and medium enterprise (SME) sector, while an essential part of any economy, tends to have limited access to and influence in policymaking. Structured dialogue initiatives should therefore make special provision to obtain input from SMEs. In 2011, Senegal’s largest, most representative business association, l’Union Nationale des Commerçants et Industriels du Senegal (UNACOIS), engaged its SME members in dialogue with government. UNACOIS divided its national membership into four regions – North, South, Centre and West – and conducted regional dialogue sessions for its members in each region.12 Complementing these discussions were two cross-regional business agenda forums that synthesized regional policy concerns into a policy recommendations document.

The Senegalese government adopted the association’s recommendations to establish a more uniform, equitable, and proportional tax code that better integrates the SME sector into the formal economy. In addition, UNACOIS worked with the Ministers of Tax and Customs, Commerce and Industry, and the Prime Minister to create a Memorandum of Understanding, which establishes ongoing dialogue on SME concerns and on the country’s persistent food security challenges.

Dialogue in fragile and conflict-affected states (Nepal) PPDs can play a special role in fragile and conflictaffected states (FCS) by supporting institutional development, transparency, trust building, and peace processes.13 PPDs in FCS economies serve as a means to prioritize and promote reforms that can potentially generate new investments and jobs. Bringing diverse actors together to discuss neutral issues that are sought by all can help to reinforce the peace-building and reconciliation process.14 In Nepal, for instance, the Nepal Business Forum, formed in 2008, demonstrated the ability to increase trust between sectors and address issues of post-conflict development. The forum explored several dimensions of Nepal’s business climate, including regulatory reforms related to investment, skills of the potential labor force, access to finance, and new business startups. A postcompletion evaluation of the Nepal Business Forum undertaken by the WBG’s Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) found that promoting PPD around private sector reforms in the context of a country struggling to establish democracy has been useful.15 By the end of the project’s second phase, results included: implementation of more than 41 of 120 recommendations; (US) $5.67M in private sector cost savings; and establishment of public-private and private-private dialogue in an environment of significant political turmoil.16

Dialogue between business and political parties (Pakistan)

An independent business gathering can evolve into a platform for public-private dialogue. Chambers of commerce have become engaged advocates for improvements to the business environment in Pakistan through PPD. Since 2009, the Rawalpindi Chamber of Commerce and Industry (RCCI) has been organizing the All- Pakistan Chamber Presidents’ Conference on an annual basis. This has become an important venue for bringing together the business community from across Pakistan to discuss pressing economic issues and propose reforms to provide a level playing field for businesses to grow.

Participants in the 5th annual conference, held in February 2013, included chamber presidents, government officials, and representatives responsible for economic policy from all five of Pakistan’s major political parties. This was a first in Pakistan, as political parties engaged directly and transparently with business leaders on the crucial need for economic reform. At the end of the conference, the chamber presidents issued their annual joint “Bhurban Declaration” of reform priorities. Then, in what was another first for Pakistan, political parties produced economic platforms which were presented to the business community and voters as part of the election campaign.

The 6th annual conference focused on holding the newly-elected democratic government accountable for its promises.17 A local think tank, Policy Research Institute of Market Economy (PRIME), developed a scorecard18 for tracking progress in three key policy areas: economic revival, energy security, and social protection. PRIME’s periodic tracking reports have received much attention from the media and helped guide the conversation with policymakers during the PPD forum at the All-Pakistan Chamber Presidents’ Conference. The Pakistani business community continues to evaluate the government’s progress in implementing economic platform promises.

Establishing Effective Dialogue

While the promise and relevance of dialogue have never been greater, it goes without saying that PPDs must strive for a high standard of effectiveness and legitimacy. Many dialogue initiatives never deliver as intended, and there are risks of the dialogue being captured by narrow interest groups or fractured without achieving meaningful results. The challenges can be mitigated, though, by good design, adequate support, appropriate monitoring, and by working through problems via the dialogue process itself. Practitioners are advised to follow the PPD Charter of Good Practice19 and learn from international experience.

In general, a PPD framework should be based on a set of tools that help to: identify the collaborative governance gaps, secure political will for reform, set up a multi-stakeholder dialogue process around the issues at stake, and ensure supportive buy-in and monitoring from constituents at large. Collectively, these tools help unlock systems where capture and cronyism are prevalent, so as to reduce corruption, remove barriers to entry, enable open competition, and improve service delivery to constituents.

One of the issues for policymakers, stakeholders, and development practitioners alike is that for PPD to eventually bear fruit considerable planning and investment must go into a structured dialogue process. Each PPD is unique and has to be tailored to local issues, institutions, and experience. Regardless of the specific circumstances, practitioners who stay attentive to the following points will remain focused on promoting high-quality dialogue.

Champions

Champions from both the public and private sectors take ownership of the dialogue process and drive it forward. They must be credible and perceived to have the broad interests of the country at heart. Public sector champions must have sufficient authority and be sufficiently engaged in order to demonstrate political will. Business champions must be independent and recognized by the broader business community as qualified to speak on its behalf. In each sector, the presence of a core leadership group is important for mobilizing and coordinating participation, and avoiding overdependence on individuals.

Representation

For a PPD to be effective and representative, it must accommodate the diversity of private sector interests. PPDs should strive to be inclusive of various kinds of firms, of different sizes and from different sectors, including global and local players, domestic and foreign, and formal and informal firms. Independent business associations act as key vehicles for articulating business views and facilitating collective action. Facilitators should seek out associations that promote market solutions— instead of seeking economic rents—and make allowance for unorganized interests to participate as well.

Transparency

Transparent dialogue inhibits collusion (or the appearance of collusion), reinforces accountability, and empowers all constituencies to make informed contributions. An institutionalized policy process clarifies what will be decided and establishes channels for participating in those decisions. Government should disclose the reform proposals being considered and any policy-relevant information. PPD leaders should run an outreach and media campaign to ensure open access and educate the public about the objectives of reform.

Preparation

Substantial capacity is required to prepare policy recommendations, negotiate constructively, collect feedback, analyze evidence, and organize overall dialogue. While a variety of responsibilities for organizing dialogue may fall on the facilitator, investing in the capacity of private and public representatives is crucial. The private sector needs capacity for researching, assessing, and coordinating businesses’ needs and views. Government needs to ensure that it has the expertise and resources to analyze policy, formulate coherent reform strategies, and communicate with stakeholders.

Sustainability

Sustainability entails integrating PPD with existing local institutions and ensuring that donors or third-party facilitators do not displace local actors and structures. Steps for assuring sustainability of dialogue include planning early for transition, building capacity, securing ongoing financing, and respecting local ownership of the process. Efforts to build sustainability into the design of PPD from the start serve to bolster the credibility of the overall endeavor.

PPD Community of Practice

Practitioners need not be overwhelmed by the complexity of PPD, as a wealth of tools and advice have been accumulated, beginning with the PPD Handbook.20 In order to support practitioners and spread PPD lessons more broadly, the global community of practice devoted to PPD can also build on the extensive networks of practitioners who gather around a new online hub, www.publicprivatedialogue.org. The hub shares tools, cases, and lessons from around the world. The community of practice supports knowledge exchange among PPD practitioners with the objectives of enabling learning and innovation, expanding the knowledge base, and spreading awareness and news of PPD initiatives.

How can PPD practitioners stay engaged, share knowledge and tools, and seek technical assistance?

Visit PPD hub: www.publicprivatedialogue.org

Connect on Facebook: facebook.com/ publicprivatedialogue

Follow on Twitter: twitter.com/PPDialogue and tweet using #ppdialogue hashtag

Endnotes

1 Joint statement on expanding and enhancing public and private co-operation for broad-based, inclusive and sustainable growth (Busan, November 11, 2011)

2 Guide to the Monitoring Framework of the Global Partnership (Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation, 2013).

3 The workshop has been organized by the World Bank Knowledge Learning and Innovation (WBKLI)’s Private Sector Engagement for Good Governance (PSGG) program and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in collaboration with the International Finance Corporation and the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation. It is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

4 Review of World Bank Group Support to Structured Public- Private Dialogue for Private and Financial Sector Development, commissioned by the International Finance Corporation, April 2009.

5 Benjamin Herzberg, 2013.

6 “Impact Assessment of the Public-Private Dialogue Initiatives in Cambodia, Lao PDR, Vietnam,” commissioned by the International Finance Corporation and AUSAID, 2007.

7 “Impact Assessment of the Public-Private Dialogue Initiatives in Cambodia, Lao PDR, Vietnam,” commissioned by the International Finance Corporation and AUSAID, 2007.

8 “Public-Private Dialogue for Sector Competitiveness and Local Economic Development: Lessons from the Mediterranean Region.” A report produced by The Cluster Competitiveness Group, S.A. for the Public-Private Dialogue program of the Investment Climate Department of the World Bank Group, and funded through the Catalonia (COPCA)/ IFC Technical Assistance Trust Fund, November 2011.

9 Amal Hijazi, “The Jordan Valley Water Forum,”

presented at the Public-Private Dialogue 2014 Workshop (Frankfurt, March 3-6 2014).

10 Teodora Mihaylova, “Public-Private Dialogue in Moldova,” forthcoming in Strategies for Policy Reform, vol. 3 (CIPE, 2015), available online at http://www.cipe.org/publications/detail/public-privatedialogue- moldova.

11 Teodora Mihaylova, “Senegal’s Small and Medium Enterprise Sector and Public Private Dialogue,” forthcoming in Strategies for Policy Reform, vol. 3 (CIPE, 2015).

12 Besides CIPE, GIZ has been a major supporter of an SME-oriented public-private dialogue in Senegal.

13 World Bank Group, “Public-Private Dialogue in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations: Experiences and Lessons Learned” (World Bank Group, 2014), available online at www.wbginvestmentclimate.org.

14 “How Firms Cope with Conflict and Violance, Experiences from Around the World,” Private Sector Development, World Bank, 2014.

15 “Nepal Investment Climate Reform Program (557305).” Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) Note 2011, IEG, World Bank, Washington, DC.

16 Nepal Investment Climate Reform Program, International Finance Corporation.

17 Hammad Siddiqui, “6th All-Pakistan Chamber Presidents’ Conference Brings Business Community Together,” January 2014, http://www.cipe.org/blog/2014/01/06/6thall- pakistan-chamber-presidents-conference-brings-businesscommunity- together/.

18 Pakistan Economic Policy Scorecard, http://govpolicyscorecard.com.pk/.

19 “Charter of good practice in using public-private dialogue for private sector development,” adopted by DFID, OECD, World Bank and IFC at the international workshop on Public-Private Dialogue, Paris, February 2006.

20 Benjamin Herzberg and Andrew Wright, The Public- Private Dialogue Handbook: A Toolkit for Business Environment Reformers, (DFID, World Bank, IFC, OECD, December 2006).

Kim Bettcher leads the Center for International Private Enterprise’s Knowledge Management initiative, which captures lessons learned during 25 years of democratic and economic institution-building around the world. The program identifies the core ingredients of successful reform projects, offers practical guidance in program design and implementation, and facilitates knowledge-sharing among CIPE partners and staff. Bettcher has written and edited numerous resources for CIPE, especially the case collections Strategies for Policy Reform, volumes 1 and 2, toolkits on anti-corruption and corporate governance, and the CIPE Guide to Governance Reform: Strategic Planning for Emerging Markets. He also co-authored CIPE’s 25-Year Impact Evaluation. Bettcher has published articles in the Harvard Business Review, Party Politics, SAIS Review, and the Business History Review. He came to CIPE from the Harvard Business School, where he was a research associate. Bettcher holds a PhD in political science from Johns Hopkins University and a bachelor’s degree from Harvard College.

Benjamin Herzberg is Program Lead at the World Bank’s Leadership, Learning and Innovation Vice- Presidency. Before joining, he led the World Bank’s Open Private Sector platform at the World Bank Institute where he worked on private sector engagement for good governance through open data and collaborative practices. Prior, he was Senior Private Sector Development Specialist in the joint World Bank / IFC Investment Climate Department, where he was the Global Product Leader on Public-Private Dialogue. Since he joined the World Bank Group in 2004, he led or participated to interventions on investment climate reform, multi-stakeholder dialogue, and competitiveness in more than 20 countries. He also led the incubation of a new Global Practice on Competitive Industries in 2010-11 and directed Investment Generation programs in Europe and Central Asia out of Vienna, Austria in 2009-2010. Beforehand, he worked in Bosnia and Herzegovina at the Office of the High Representative on participatory reform making and at the OSCE on stimulating the SME sector. Previously he worked in the private sector in France (banking), Israel (biotechnology) and the USA (high-technology). Herzberg holds a post-graduate degree in Geography and Environment from the Université des Sciences et Techniques, and a Suma Cum Laude master’s degree in Geography from the Université de la Sorbonne, France.

Anna Nadgrodkiewicz is the Director for Multiregional Programs at the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) in Washington, DC. She leads programs spanning emerging and frontier markets in different regions focused on CIPE’s core themes of democratic governance, legal and regulatory reform, access to information, combating corruption, property rights, entrepreneurship, and women and youth. Her expertise also includes association capacity building and governance. Nadgrodkiewicz has authored and co-authored numerous publications addressing the challenges of political and economic reform around the world and is a regular contributor to Thomson Reuters TrustLaw blog. Prior to joining CIPE, she worked as a business consultant in her native Poland on the issues of competitiveness and market entry in Central and Eastern Europe, and in Washington, DC on industry benchmarking and corporate strategy. She holds a BA from Indiana University of Pennsylvania and a master’s degree in German and European Studies from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service with the honors certificate in International Business Diplomacy.