The Issue: Experience of PPD in recent post-conflict situations – noticeably Sierra Leone, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Liberia, with further examples in Kosovo, East Timor, and other countries – points to its significant potential as a tool for promoting peace and expediting the reconstruction of civil society.

- Because they focus on the specific and tangible issues of entrepreneurship, economic reconstruction and investment climate improvement leading to job creation and poverty reduction, public-private dialogue initiatives are very effective at building trust among social groups and at reconciling ethnic, religious or political opponents.

- PPD can be especially valuable in enabling the sharing of resources and building capacity – a particular priority in crisis environments.

- Structures and instruments for dialogue need to be adapted to each post-conflict or crisis context. They need to take into account the inherent informality of the economic actors and the potential role of customary systems in re-establishing the rule of law.

- An external “honest broker,” possibly linked to international organizations in charge of peace building, may be needed to kick-start dialogue. But mechanisms should be put in place for quick transfer of the initiative to local ownership.

C.11.1. Post-crisis PPDs face specific challenges

Some investment climate problems are likely to be more pronounced in post-conflict or post-crises countries. They include:

- limited formal access to finance and weak public sector capacity to regulate, leading to a concentration of private sector activity in the informal sector;

- scarcity of land for development and deficient infrastructure services;

- lack of management and technical business skills in the private sector, and lack of business development services;

- instability and concerns about security leading to rapidly changing situations and unpredictability;

- lack of social capital and high levels of mistrust;

- breakdown of links with external markets, and the perceived high political and business risks of re-engaging; and

- absence of an effective court system to enforce creditor’s rights and contracts.

PPD in post-conflict environments is therefore likely to require particular strengths in most of the following areas:

- government commitment;

- strong champions and effective facilitators who are perceived as neutral;

- simplicity and flexibility of design to adapt to unanticipated opportunities;

- attention to capacity building programs in both public and private sector; and

- outreach and communications strategy to build social bridges and emphasize commitment to

common goals.

C.11.2. Some PPD benefits are increased in post-conflict

C.11.2.1 Reconstruction

Dialogue on investment climate concerns, pursued in targeted local regions, can facilitate reconstruction and build confidence from the bottom-up. Involving local constituencies in reaching consensus on policy design and then reaching targeted results can provide for “good news” early in the reconstruction process as well as solid benchmarks for evaluation and monitoring. Such “quick wins” are reached, the reconstruction benefits are multiple:

- The results being speedier, especially compared to systemic reform efforts usually applied in post-conflict situations, they empower local groups and demonstrate outsider bona fides.

- They propel economic development forward at local level.

- They can jump-start post-conflict institutional development.

- They can sharpen donor, international community, and central government responsiveness

through dialogue.

C.11.2.1 Peace building

PPD can serve as a platform to reach broader post-conflict goals:

- PPD processes can be used as dispute resolution and conflict prevention tools.

- Through communications, they help international or central government messages reach all

segments of the population, up to the local level; PPDs also provide a mechanism for local concerns to be communicated upwards. - Dialogue can build the basis for reconciliation by addressing societal issues such as respect for human rights, and for addressing broader issues such as corruption and combating organized crime.

- Stable dialogue can lay the basis for refugee and internally displaced people (IDP) return.

C.11.3. Applications

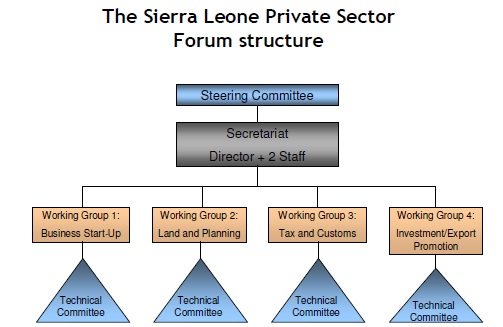

C.11.3.1. Sierra Leone: Peace dividends of the Private Sector Forum

A donor-led post-conflict diagnostic study on the investment climate revealed some of the fissures and sensitivities within the government. The solution design (action planning) phase discovered that the focus on economic reforms through the removal of administrative barriers to

investment could be a useful tool for bridging these gaps, by turning the process into a multi-ministerial-led project. To this end, the project established an Inter-Ministerial Subcommittee, led by the Minister of Trade and Industry, which unanimously endorsed the implementation plan.

Additionally, it became clear during the diagnostic phase that the private sector was not unified in the push for reform, and that it tended to be divided along ethnic lines. Again,

during the action planning process, these disparate groups began to work together, actually culminating in the creation of an ad-hoc business forum. Maintenance of this dialogue was critical to the success of the reforms, therefore the Sierra Leone Business Forum was formed. Led by the Minister of Trade and Industry, it became a key source for designing and implementing the investment climate action plan.

An interesting feature of the forum is that this nascent public-private group was designed to be a vehicle for dialogue not only between the government and the business community, but also between the different groups within the business community.

C.11.3.2. Liberia: The challenge of reconciling ethnic-based business associations

In 2006, three factors play against coordination of business associations: First, due to the extended conflict, most business associations had historically been entrenched in defending specific ethnic groups rather that investing time and resources in coordinated policy advocacy. Second, the hold of some business associations on large parts of the informal sector had created a vested interest in the status quo. Third, the opposition over the citizenship restrictions, land ownership, and liberianization act (excluding foreign ownership in 26 sectors of the economy) had caused bitterness on both sides.

The Foreign Investment Advisory Service (FIAS) of the IFC served as a neutral partner to bring together business advocates representing all the different ethnicities, a first since the end of the civil war. Discussion took place between the different parties on ways to organize better for being more effective vis-à-vis the government. All present avowed the ineffectiveness of their policy advocacy strategies and acknowledged that they had more issues in common than differences. They decided to unite forces in presenting reform proposals in a single voice. They demanded technical assistance in organizing themselves, as they recognized that past conflicts called for neutral coordination of the different groups rather that having one group taking the leadership in term of coordination and logistics. All associations also expressed the fear of possible retaliation from government officials if they came forward with reform proposals that would reduce or eliminate rent collection for such officials. Thus the idea of creating a new initiative, in parallel to the existing Chamber of Commerce was extremely appealing to all, as it gave all association the ability to “hide” behind a neutral brand so that individual associations or entrepreneurs could not get singled out.

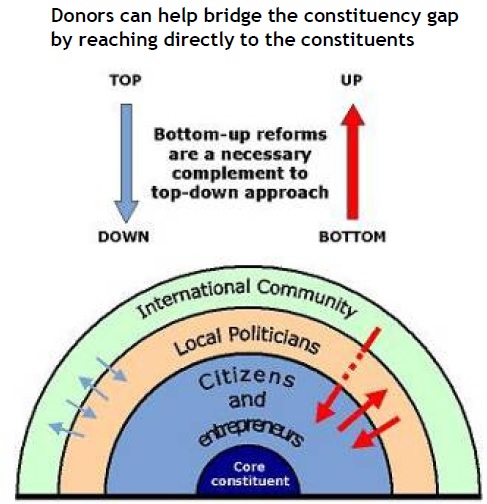

C.11.3.3. Bosnia and Herzegovina: Bridging the constituency gap

In post-conflict situations, international institutions or third-party countries often take the lead in establishing macroeconomic stability, promoting the rule of law, developing the private sector and building institutional capacity. The natural partner of the internationals for these activities is the local political leadership. This political layer often faces great legitimacy challenges, being either inherited from former systems, or facing strong skepticism by local constituents. Fighting for their own survival, local politicians quickly understand the give and- take relationship with donors and financial institutions, who are in turn satisfied with the consensual agreement and “good will” of the local political layer. Clearly forgotten, the constituencies are not taken into account in the dialogue for reform, and fail to understand the benefits of structural (and therefore painful) changes that the country needs to go through on its way to economic recovery and political stability. If not cared for, the “constituency gap” can promptly lead to social unrest, or at least lack of support for reform and disillusion with the benefits of peace.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bulldozer Initiative succeeded not only in introducing important reforms but also in bridging the constituency gap by empowering and training local groups to advocate change, and in establishing sustainable democratic mechanisms for civic

participation in government. Once established, the PPD broke through political and ethnic barriers, and created a coherent and sustainable link through a new democratic dynamic. According to the International Crisis Group, the Bulldozer Initiative actually “create[d] an alternative constituency for reform, which does not rely just upon the national parties”.15

C.11.3.5. Cambodia: Overcoming mistrust through structured dialogue

In 1998 peace came to Cambodia after almost thirty years of war. The war had been concluded in phases from the Vietnamese entry to Cambodia in 1979, the involvement of the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) culminating in a general election in 1993, and finally the complete cessation of hostilities in 1998.

Throughout the concluding decade of the war the government had become focused on instituting a market economy in Cambodia. Although there had been some early success with the rise in the garment sector, by the late 1990s the Asian financial crisis affected Cambodia and this led to a realization that the emerging private sector needed to be included in the development of the economy if it was going to grow.

Once this recognition was made, Cambodia initiated the Government-Private Sector Forum (G-PSF).

Cambodia’s G-PSF is a public–private consultation mechanism. The forum is held biannually under the chairmanship of the Prime Minister of Cambodia. The G-PSF is a full cabinet meeting and the decisions made in the Forum are binding as such. The G-PSF is an opportunity for the private sector and the governments to report on the progress of the seven Working Groups and to consider the outstanding issues that remain unresolved from the WG meetings. The seven Working Groups are the engine of the G-PSF. They are organized by sector: 1) Law, Tax and Governance, 2) Export Processing and Trade Facilitation, 3) Services, including Banking and Finance, 4) Tourism, 5) Manufacturing and SMEs, 6) Agriculture and Agro-Industry, 7) Energy and Infrastructure. Each Working Group is co-chaired by a Minister of the Royal Government of Cambodia and a representative from the private sector. The Working Groups meetings discuss an agreed agenda of issues and recommendations that relate to either policy (e.g. laws, sub-decrees, prakas, decisions) or direct operational impediments confronted by the private sector (such as road conditions, unofficial fees, damaged infrastructure). Outstanding issues that are not resolved within the Working Group dialogue are referred to the G-PSF for Cabinet review.

As the Working Groups meetings are attended by representatives of the line ministries, one of the important functions of the G-PSF is that it provides an opportunity for intragovernment exchanges of information relating to private sector development.

When this mechanism was put in place, deep distrust existed within the community. The privations experienced by Cambodians under successive communist governments made them cautious with regard to business or personal exposure. An open dialogue between government and private sector was something new to the emerging private sector.

An important factor that enabled the Forum to move forward was the focus on a neutral, shared, nonpolitical platform which could be used for constructive consultation on issues, not criticism. If the Forum had been perceived as other than a constructive, participatory process that was understood and appreciated as such by the government, it would not have encouraged businesspeople to engage in a participatory process for development.

From an early narrow base of participation, and sometimes difficult consultations, the G-PSF has continued to evolve to provide a structure for private sector participation. As a process that depends on personalities and building relationships where they otherwise had not existed, the process needs to be constantly worked with to build a trust-based dialogue focused on private sector development.

C.11.3.4. Other nascent or potential applications

Private sector development is critical if countries are going to move away from war and provide

opportunity for conflict-afflicted populations. An inclusive, participatory approach such as that being developed in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Bosnia and Herzegovina, or Cambodia can play an important role in such development.

Because of their considerable contribution to the growth of civil society, PPD processes could be designed for example in Afghanistan to bring previously repressed segments of society into the political culture by engaging them in the identification of administrative and economic reforms relevant to their daily lives. Through this process, small farmers and women could develop a sense of ownership and pride and increase their power as constituents.

In Kosovo, a public-private dialogue methodology is being applied since July 2004. The Kosovo Bulldozer Committee is sponsored by USAID and the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). It involves a dialogue between the Alliance of Kosovar Businesses and the Provisional Institutions of Self- Government, with an aim of identifying regulatory burdens that slow investment down and hinder business operations. This partnership effort was launched as it was recognized that “not just economic growth but political stability”16 depend on the success of such undertaking.

In Iraq, appealing to small entrepreneurs for reforming administrative procedures and rewriting commercial rules and legislation could help in reconstruction of a legal framework. In addition to filling in the gaping holes in private sector regulation and boosting a business-oriented middle class, this process would provide much needed legitimacy, coming from the Iraqi private sector rather than from the immediate corporate interest of reconstruction contractors.

Timor Leste has been independent since 2002. Despite the recent resurgence of violence in spring 2006, private sector associations are attempting to federate themselves into a business forum and organize a constructed dialogue with the government. With 80 percent of the economy being informal, how representative such a forum can be remains an issue. But with weak property rights, inefficient registration, difficult trade regime and a complicated tax system, businesspeople have little choice but to advocate with the government for a betterment of the business environment. Donors, such as the IFC, intend to help in building capacity for the steering committee.