The issue: Dialogue usually doesn’t happen unless someone really wants it to. A common hallmark of successful PPDs is that they have strong and effective “champions” driving the process forward – but not so strong that they skew the process or make it personally dependent on individuals.

It is difficult to sustain dialogue without champions from both the public and private sectors who invest in the process and drive it forward.

- Backing the right champions is the most important part of outside support to PPD.

- It is easier for dialogue to survive weakness of champions in the private sector than the public sector.

- If champions are too strong, the agenda can become too narrowly focused, or dialogue can come to depend too heavily on individuals.

- Champions need to see the bigger picture and understand when they need to take a step back.

C.3.1. Use stakeholder mapping exercise to identify potential champions

Good champions can come from public or private sectors, the donor community and even civil society – Nigeria’s Better Business Initiative, for example, arose largely from the championing of an academic who was highly respected in both business and government circles.

The most important qualification for champions is that they are widely perceived to have the broadest interests of the country at heart. Elected business association members are more likely to fulfill this criterion, especially if the association represents a wide range of businesses, than individual businesspeople.

Nonetheless, there will often be successful individual entrepreneurs who are widely perceived as being capable of speaking for enterprise in general, rather than their own interests in particular. An important function of the stakeholder analysis described in the introductory diagnostic section is to identify such dynamic and public-spirited entrepreneurs.

C.3.2. Government champions should be seen as taking a wider view

Because champions need to be perceived as taking a wider view, ministries that provide direct services to the private sector – such as Ministries of Industry who run direct credit programs or business services operations, or Ministries of Commerce whose funding depends on license fees – need to be strong and well-regarded to function effectively as champions.

Ministries whose primary mission is the protection of civil society (such as Health, Education, Labor, Environment) generally tend to make poor champions, but are essential participants in PPD.

The most effective public sector champions often tend to be presidents or prime ministers, mayors or regional leaders – not only because it helps to have high-level political backing, but because they are most likely to be seen as taking an overall view of societal benefit.

C.3.3. Roles and responsibilities of champions

Champions can play important roles both behind the scenes and in the media spotlight. They may be most useful as “fixers” who can quietly persuade reluctant potential players to get around a table. Or they can be high-profile cheerleaders for dialogue – motivating SMEs to get involved, or assuaging public skepticism about the purpose of dialogue.

| Typology of champions | |

|---|---|

| Donors | At their best, donors can kick start the reform process when political consensus is lacking. They can provide resources, facilitate, and promote awareness, understanding and commitment to reform. They can also help create new champions in the system. |

| High level political champions (e.g. ministers or private sector leaders) | High profile, well respected and able to gain credibility among different stakeholders. Good understanding of the importance of the private sector. |

| Senior level, but less visible (e.g. permanent secretaries, parliamentarians) | Work more “behind the scenes”, but with the authority and gravitas to make things happen. |

| “Energetic” champions | Often leaders of NGOs or BMOs who can inspire grassroots enthusiasm but are less able to remove obstacles at senior levels of government. |

| “Reluctant” champions | Bureaucrats who will have to implement reforms can sometimes become enthusiastic when offered training and career-building opportunities. |

| Individual entrepreneurs | The right mechanism can enable individual entrepreneurs to become champions for reform – usually in the form of collective action, but occasionally individuals breaking the mold can set an example to peers. |

C.3.4. Identify different champions for different issues and target audiences

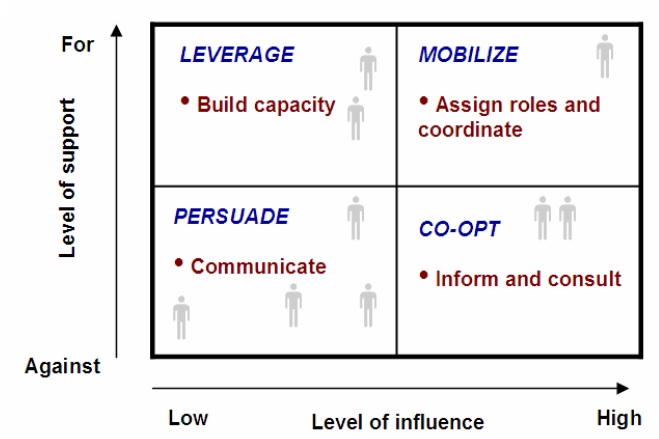

The stakeholder analysis matrix helps to identify different stakeholders who need to be approached in different ways – leveraged, mobilized or neutralized. This matrix should be used as a basis for identifying champions to perform specific roles with regard to specific groups of stakeholders.

For example, if the matrix identifies SMEs as pro-dialogue but relatively powerless and labor unions as anti-dialogue and powerful, quite different champions may need to be identified to leverage the former and co-opt the latter.

C.3.5. Providing support to champions

Donors or other initiators or managers of PPD should consider the needs of different types of potential champions, and ways to empower them as change agents. This means understanding the local context, and focusing on the dialogue process rather than being prescriptive about the reforms it might lead to. It means adopting a flexible approach to engaging with champions and being prepared to “go the extra mile.”

When donor agencies are involved in engaging with champions, it is especially important for them to recognize that this is a two-way exchange, and as such is an important learning opportunity for donor agencies themselves.

Important factors in providing effective support to champions include:

- Respect for local context

Some local champions may prefer to engage with PPD staff from their own culture, others may value the external perspective offered by international staff. It can often be the case that senior champions may resent being supported by younger, less experienced staff. Gender sensitivity must also be central to engaging with local champions. - People skills

PPD mechanisms may employ staff or consultants on the basis of competence in their fields of specialization, but dealing with champions also demands adeptness at the human side of engagement. In this sense, training may be needed for PPD staff in mentorship, facilitation, change management, training trainers or information and communication skills.

Especially important for international staff or consultants is to understand and value their privileged position as neutral advisors with the benefit of experience from international best practice, and less directly affected – although by no means unaffected – by the immediate pressures of local, political, social, and cultural influences.

This affords a number of advantages. First, it means international staff should benefit from greater clarity in helping champions to construct a message that makes the link between the proposed reforms and the benefits to those affected.

Second, where a difficult or uncomfortable reform needs to be promoted it also means international staff is well placed to help champions construct a coherent and well balanced justification for the need for reform.

Third, international staff should be able to draw on their experience to support champions insetting achievable goals and recognizing progress or setbacks to the change process.

- Sustaining commitment

Often, champions are taking a risk in promoting and supporting PPD. It is therefore vital that initial political will is carried through into practical support, including efforts to build supportive networks that will leave champions feeling less isolated.Basic equipment and supplies should not be ignored. Something as basic as the lack of a photocopier can be the difference between a change agent being able or unable to promote a message among his or her colleagues. - Capacity building

Over the longer term, champions can benefit from capacity-building activities. Study tours are often criticized as ineffectual and a drain on limited resources, but when done well they can expose champions to new ideas and new ways of thinking.

Training opportunities can also expose individuals to new thinking, and can have even greater sustainable impact if those individuals are then empowered to become the trainers.

Sustaining commitment in practice

In Moldova, the BIZPRO programme, funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has translated political will to reform the legal and regulatory environment for doing business into a coherent strategy and action plan supported by a specific mechanism (the Regulatory Guillotine) for delivering short-term results in order to sustain momentum for reform.

The credibility of government has been bolstered by the delivery of “quick wins” and government has positioned itself as a driving force in the reform of the business environment through the use of a well-targeted media campaign and regional workshops. (See www.bizpro.md for more details.)

In Uganda, the DFID-funded Regulatory Best Practice programme has provided capacity-building support across the public-private divide by providing training and mentorship to government policy analysts and to BMOs.

The programme has focused on building a common language of reform around the concepts of Regulatory Best Practice (RBP), which has helped to build more constructive engagement and a partnership approach that is starting to bridge the divide between the public and private sectors.

C.3.6. Making best use of champions for media reports

When designing an information and communications strategy to promote a reform or dialogue platform, it is important to consider how to engage champions as messengers and which champions will be most effective in promoting your message. The audience that a PPD is trying to reach should determine the choice.

A number of types of champions could be particularly effective, depending on the audience. On the one hand, high-profile, well-respected champions can be used to write editorials, for example, that could prompt government into the desired response.

On the other hand, the individual stories of entrepreneurs can have a strong impact, particularly when profiled on a regular basis, as this helps to convey the message that there is a problem that needs to be addressed. The use of individual entrepreneurs can also have a popular appeal as more citizens can relate to their experiences.

There are also some important considerations to bear in mind when selecting champions for a media campaign. High-level, influential political champions both in and outside government can be generally sensitive to media use, particularly in environments where certain sections of the media are seen less as an information and education platform and more as a trouble-maker for government.

In addition, such high level champions – especially those engaged in PPD – are often media-shy because they fear being unfairly judged as being unable to keep confidences. For related reasons, the “reluctant champions” identified in the champions typology, above – those civil servants with a vested interest in not being seen to rock the boat publicly – may be reluctant to become high-profile messengers of reform.

The “energetic champions” described in the typology – the leaders of NGOs and BMOs who may have a good story to tell and plenty of evidence to tell it with – may also not be the most effective messengers in environments where there continues to be a deeper reservoir of mistrust between government and civil society.

Taking these sensitivities into consideration, the most effective messengers may be the individual entrepreneurs with a personal story to tell that most citizens can relate to, and who often lack effective mechanisms for having their voices heard by government.

C.3.7. Be flexible in choosing champions to respond to changing circumstances

Three factors are likely to inform how one engages champions, bearing in mind the certainty that circumstances will change over time.

- First, it is important to identify probable champions early in the reform process – the changing political landscape or the results of public service reform can create the risk of “backing the wrong horse” if a chosen champion becomes marginalized or moves on from office. There is also often a strong case to be made for letting champions emerge.It is important to observe which individuals exhibit initial keen interest in an issue. Before choosing to engage with individual champions, it is important to be sure that he or she will be willing to take a risk even without the support and backing of a donor – and that he or she has some existing influence.

- Second, today’s champion can quickly transform into tomorrow’s opponent. Individual issues within reform processes can be the catalyst for a loss of support from individuals who were previously considered to be proponents of reform. To tackle this, it is important to be clear about focus and likely impact of reform right at the beginning.If a champion’s support is premised on inadequate understanding and appreciation of reforms, the champion may become a potential spoiler. Avoid champions whose initial interest is based on expected personal benefit, as they will be likely to desert the reform process if they do not secure a sustained personal advantage.

- Finally, it is helpful to acknowledge that champions more often than not will have a shelf life, and there is a risk of the champion outliving his or her usefulness. At the same time, this needs to be balanced with a responsibility to providing support to chosen champions.Given that most PPDs change over time, we should also expect champions to change accordingly. The relationship with the PPD must be continually renewed to ensure that all parties remain relevant to each other and continue to be in a win-win situation.