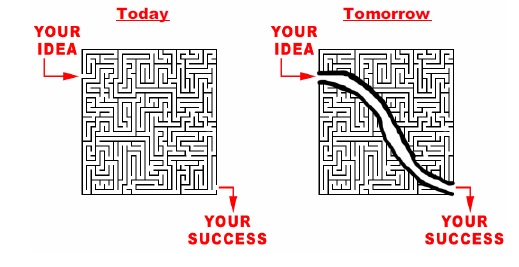

The issue: The public and private sectors often enter into dialogue with different worldviews, assumptions, and vocabularies. Many entrepreneurs who have value to add to dialogue may choose not to involve themselves in the process because of a lack of awareness or appreciation. Interactions between governments and businesses are also open to unfavorable interpretation by others, especially when the criteria for selecting business participants appear to be opaque.

stakeholders.

- Common communication requires a mutual understanding of core motivation, which depends on frequent and iterative interactions between all parties.

- Dialogue should be as open-access and broadly inclusive as feasible. This necessitates an outreach program to the reform constituency. Elements can include use of the media, seminars, workshops, and roadshows.

- This also necessitates attention to building the capacity of the private sector to participate in dialogue to achieve a concerted strategy to communicate reform issues through clear and targeted messages.

- Transparency of process – in particular, an open approach towards the media – is essential for outreach, and also contributes to measurement and evaluation.

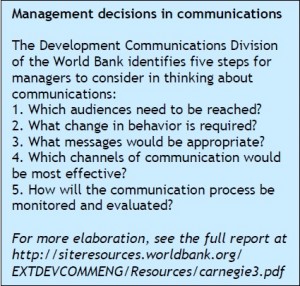

C.6.1. Communication strategies must be both for participants and the general public

The more successful PPDs tend to have effective communications strategies for making participants and the general public aware of the returns on the time and effort invested in dialogue.

C.6.A. Outreach

C.6.A.1. Build the capacity of BMOs

BMOs are a great means of reaching out to larger numbers of entrepreneurs – but they are often weak, ineffective, or non-existent.

There are many ways to foster capacity building in BMOs. One of the main obstacles to overcome is often the lack of trust the business community can have in its own BMOs, especially if these – as sometimes happens for Chambers of Commerce – have been set up by governments.

Indeed, for a government to make membership mandatory – which is often the case in countries transitioning from a socialist system – does not guarantee that mandatory subscription fees will be used wisely in representing members.

Instead, governments can help to make membership of BMOs attractive by providing incentives such as loan guarantees, special financing, and procurement opportunities. Find out more about strategies for strengthening BMOs in Building the Capacity of BMOs: Guiding Principles for Project Managers.

C.6.A.2. Direct outreach to entrepreneurs helps to elicit good ideas

Existing institutions often fail to harness the energy and ideas of grassroots entrepreneurs. This can be done by inviting them to submit proposals on a simple form, as outlined in the previous chapter.

Awareness of the form, or more generally of the PPD and its intended outcomes, can be raised through a media campaign and traveling road shows. All submissions should be considered transparently and everyone who submits proposals should be kept informed about their progress. The risk of personal exposure of entrepreneurs fearing to be perceived as trouble-makers by their governments, can be mitigated if the PPD initiative has a strong brand, behind which the entrepreneur can be anonymously represented or feel more secure.

The promoters can also be more aggressive in obtaining ideas by conducting surveys of businesses (for instance BIZPRO – under USAID funding – in Ukraine conducts a regular survey of SMEs) or even of government employees.

C.6.B. Branding

C.6.B.1. Branding and visual images have power

Re-branding Nigeria’s “Competitiveness Forum Working Group” as the “Better Business Initiative” helped to communicate its core values to its target audience. .Similarly, the name “Gender Coalition” in Uganda communicates very well the topic of the PPD.

The name, “Bulldozer Initiative” in Bosnia and Herzegovina, indicates a sense of urgency in dealing with regulation. The “Government Private Sector Forum” in Cambodia communicates the nature of the actors taking part in the partnership, while giving a clear idea that dialogue is the foundation of the partnership.

The power of a good name, a good logo, or powerful visual image should not be underestimated to

communicate the potential benefits of PPD aimed at improving conditions for private sector

development.

C.6.B.2. Basic notions on branding

It is important for a PPD to know the value of its brand so that it can allocate adequate resources to nurturing, building, and protecting it. As for many nonprofit organizations and consumer goods companies, a PPD’s brand is, along with its people, one of the most important assets it has.

Tracking the value of that asset and understanding which activities increase or decrease asset value is key to managing it effectively. A brand is more than just a name, logo, or trademark. Branding is an important way to connect with people.

A brand is a complex symbol that can convey up to four levels of meaning:

- Product Attributes

A brand can convey information on tangible product or service features, such as physical or functional performance, size, appearance, etc. A brand can also convey information on intangible product attributes, such as trustworthiness, prestige, etc. - Product Benefits

Clients or stakeholders are actually buying or getting “benefits,” i.e. what the product/service/initiative does for them – functionally and/or emotionally. An effective brand can convey this information as well. - Brand Values

A strong brand will establish how the product/service/initiative fits with the client’s or stakeholder’s values. It does this by saying something about the client’s or stakeholder’s values and how he/she wants to be seen by others, and associating this with the product/service/initiative. - Brand Personality

A brand will attract supporters whose actual or desired self-image matches the brand’s image.

Public-private dialogue initiatives are by nature multi-stakeholders partnerships, so they have missions and constituencies that add to the complexity of brand management.

For instance, asked what the PPD is all about, a banker would probably answer that the initiative is aimed at facilitating the growth of personal and business finance in the country. Someone with gender equality concerns may consider the PPD as a vehicle to promote gender neutrality in the business environment. Politicians may view the same partnership through yet another pair of eyes, considering it as an institutional mechanism to push for reform in need of a grassroots constituency.

C.6.B.3. Creating a name

All these aspects need to be taken into account when producing names or visuals for a PPD initiative.

The two basic questions that need to be answered are: who is your audience? what are the values you want to communicate?

The name could derive from the answers. Initiators of a PPD may wish to choose words in a PPD’s name that will communicate a stronger element of one or more of the following:

- Private sector viewpoint (e.g. “business”)

- Dialogue with government (e.g. “partnership” or “forum”)

- National union and identity (e.g. the name of the country)

- Private sector frustration (e.g. “voice”)

- Private sector leadership in policy making (e.g. “initiative”)

- Private sector understanding of macro policy, and economic concerns (e.g. “competitiveness” or “investment climate”)

- Urgency and private sector impatience (e.g. “Bulldozer”)

- Goodwill (e.g. “better”)

- MSME advocacy (e.g. “micro”)

As previously mentioned, a logo should eventually be associated with the name; the logo could be made of the initials. A logo will be a very useful tool for communication purposes – media, reports, corporate identity, etc.

From top left, clockwise: The better business initiative in Nigeria, the Bulldozer Initiative in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Vietnam Business Forum, the Lao Business Forum, the Cambodia Government Private Sector Forum, the Joint Economic Council of Mauritius, Compite Panama.

C.6.C. Communication Tools

C.6.C.1. The need to communicate economic reform efforts

Competent use of the media promotes public-private dialogue and is, of itself, a function of this dialogue. This is because public and private institutions approach the media differently, and nine times out of ten private institutions communicate more effectively.

They have to: their bottom line depends on good communications. A public institution explains. A private company sells. Private companies tend to sell more effectively than public institutions explain. Because of this, private sector expertise is at a premium in communicating PPD themes to the general public.

However, the private sector, particularly SMEs, are often less savvy than public institutions when it comes to using media coverage to advance a political agenda. They understand the mechanics of selling products, but often fail to see that reforms can be sold in the same way.

C.6.C.2. Humanizing reforms

Ways must be found to humanize the reforms so that people can relate to the benefits they bring.

It is especially important to translate the technicality of reform proposals into plain language when communicating the reforms to a larger audience. Various techniques can be used,

as long as they are adapted to local language and understandings. But these types of efforts are not always required for the reform process to carry forward. Depending on the situation,

communicating to the larger public through the media with information campaign can actually

backfire. It may create more opponents than supporters.

There is however a number of success stories to learn from. In Georgia, a successful anti-corruption communications campaign was run through posters on public transport.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, every day for three months a newspaper published a column featuring a photograph of an entrepreneur and answers to a standard set of questions about how his or her business would benefit from a reform; this alone did much to further public understanding of and support for the dialogue process.

C.6.C.3. Handling the media and organizing press conferences

A basic way to communicate on the progress of a partnership is to invite members of the media to a press conference at the conclusion of a plenary session, a forum, a group meeting. If the media is well informed, either through previous briefing or carefully prepared informative handouts, the dialogue with the press can be fruitful and inform how the message could be carried out in subsequent events.

Press conference can be staged and impersonal. But if a partnership aims to build true grassroots support, a press conference should be a true dialogue with the press: unpredictable, authentic, grounded in practical advantages that the businesspeople are seeking, and focused on defining how these advantages could contribute to the general

economic good.

It can be beneficial to push forward members of working groups, even if they never have appeared on TV before or spoken to the press. It can help transform them from technicians, bureaucrats, entrepreneurs to policy advocates.

When talking to the press, people often discover that if they simply communicate the essence of proposed reforms or agendas, their arguments begin to have resonance where they want them to resonate – among the legislators whose support they need in order to enact reforms.

Press conference should establish a dialogue based on mutual interest: the businesspeople want reforms; and with all the hard work already done in terms of drafting legal amendments and working out the likely impact of new legislation, the politicians want the political kudos that goes with being labeled reformist.

If both sides have positions that are easy to understand, they will be easy to communicate. If a win-win situation can be created over the long run, media coverage through press conference should become an integral part of PPDs.

Beyond press conference, public information documents and brochures can be used to explain the process of how reform proposals are being designed by the public and the private sectors, their rational and content.

In Vietnam, the Business Forum regularly publishes its position papers and distributes them to informants.

In Nigeria, the NESG publishes the proceedings of all the summits.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, two brochures were distributed during the Bulldozer Initiative, respectively at 84,000 and 200,000 copies through 5 newspapers, as a free insert (printed

in black and white on newspaper-quality paper). The total cost for the campaign was $50,000. All the reforms promoted by the brochure got adopted 50 days after the first brochure hit

the stands.

The figure below describes the different components of this brochure.

brochure

C.6.C.5. Using comics

Another technique successfully used in Bosnia, but which has also worked well in Latin America, was a cartoon strip which ran in newspapers, dramatizing the life of an entrepreneur. This showed how the reform-enabling PPD efforts could make important changes in the lives of real, ordinary people.

The character in the cartoon strip, Max, reflected the concerns that had been expressed by businesspeople in the course of the Bulldozer process – but he also reflected a distinct personality. As his personality developed, his approach to the message developed too. The story – the fiction – was liberating, but at the same time, the character had an angle on the message – just as the real businesspeople had an angle on the original message.

One of the strengths of cartoons is, of course, that the lessons can be “humanized”.

A second campaign in the same country aimed at promoting direct elections of mayors and better

governance practices at the municipal level achieved to rally grassroots support through the serialized graphic novel telling the story of a woman-Mayor – Jasna.

Complementing the cartoons was the T-shirt. Several thousand T-shirts were produced to accompany one of the economic reform cartoons, taking the reform message into a new level of public consciousness.

The Bulldozer media campaign reflected political initiatives that promoted to a greater or lesser degree an authentic dialogue among stakeholders; the campaign was effective because it combined private sector communications expertise with public-sector political savvy – the medium was very much a part of the message.

C.6.C.6. Promoting PPD through op-eds

Opinion-editorial pieces in newspapers (op-eds) can be an especially valuable way of using the media to get a message across. PPD staff can draft op-eds for senior political and business figures and place them in the local media.

Op-eds have been found to be particularly useful where an argument has to be laid out in logical detail. Once it is published, it can be given a considerable and useful afterlife – circulated by email, photocopied and handed out to journalists, and used to sum up arguments for a particular policy at a particular time.

The op-ed is also an ideal instrument for engaging policymakers and opinion-formers on specific issues.

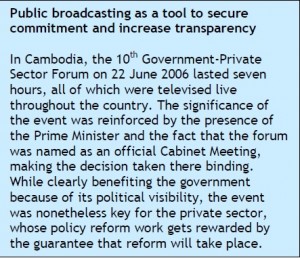

C.6.C.7. Using TV

TV appearances or regular programming brings prestige and legitimacy to a partnership. But examples of good use of TV by PPDs do not abound, as one-off successes are hard to sustain over time, and TV producing is relatively costly compared to a print, billboard or radio campaign. However, State-owned televisions may carry programs at no cost, except the cost of producing, which is often reasonable in developing countries. A live show called “Questions and Answers” in Bulgaria, related to a Local Economic Development initiative, cost only $200 per week to produce. Also, TV can be used by the PPD initiative to communicate its dealings: In Cambodia, every year, the Government-Private Sector Forum plenary meeting is actually broadcasted live during eight hours on public TV. This also helps train journalists on PPD and economic reform issues.

Shown here on promotion of an SME credit reform, “Business Edge” is a TV series in Cambodia and Saudi-Arabia which is part of a larger suite of tools to address the concerns of SME owners and managers to enhance business management skills and raise awareness on business policy-related issues. The Business Edge program was initiated by the MPDF of the IFC in December 2002.

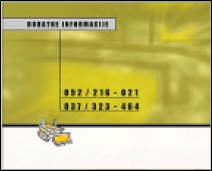

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the private sector involved with the Bulldozer Initiative decided to privately fund an ad campaign on TV, promoting the PPD objectives and providing the public with a call for action: a toll-free number was provided for citizens to reroute reform ideas and, more largely, to take part in the project. To outset the high cost of ad time, the group decided to opt for a minimum production cost by using basic video-text editing.

C.6.C.8. Using the radio

Radio is an extremely powerful medium, especially in developing economies where high cost, unreliable electricity, and poor programming is a deterrent for TV ownership. In Sierra Leone for instance, radio is the number one medium by far, as people have kept the habit of listening to constant news reports since the war. While a TV campaign will hardly reach 5-10 percent of the population, a radio campaign is likely to reach 80 percent.

An example of the power of radio comes from a reform effort in the Philippines. 9 Presenters of the most popular radio talk shows were invited to attend an informal briefing on the proposed laws at a private luncheon, followed up by informal personal contacts.

Because they understood the basic aspects of the proposed laws and the rationale for it, these presenters could ask pointed and strategically important questions on the air – and because of the size of their audience, it was difficult for any politician to decline responding to their queries.

In one incident, for instance, a legislator was asked why he seemed opposed to a bill that would help reduce corruption, with the presenter referring to his past actions in Committee; that legislator eventually voted for the bill.

C.6.D. Social Marketing

C.6.D.1. Using the social marketing framework to conceive PPD campaigns

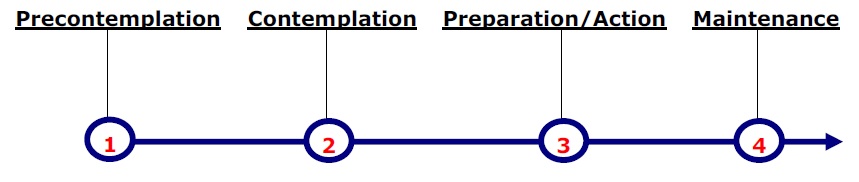

Social marketing is the name given to attempts to bring about social change by using the techniques of commercial marketing to move target audiences through the four classic stages of behavior: precontemplation, contemplation, action, and maintenance10.

1. Precontemplation: people or groups often start from not knowing that an issue at stake is a problem.

2. Contemplation: once they are presented with the facts, they move to the contemplation stage (“I understand that it is a problem, and I could do something about it if I wanted to”).

3. Action: the next stage is to get exposed to possible solutions and decide what is the one which is would represent the lower cost for the biggest benefit.

4. Maintenance: once this is achieved, action can be taken, results measured and then maintained through recurring behavior.

This framework is very applicable to economic reform and public-private dialogue in particular. Indeed, social marketing uses the techniques of commercial marketing to influence behavior. Usually, its target audience is the people who are exhibiting the problem behavior – for instance, people who smoke and don’t exercise. But social marketing can also be used to influence institutions and systems that inhibit downstream individual behavior. For example, if sidewalks aren’t lit, police protection enhanced or bike paths paved, urban residents may find it very difficult to exercise. Economic reform interventions involve influencing individuals’ behavior – whether it’s that of the legislators who have to pass laws, the regulators who have to enforce them, foundation executives who can decide whether to fund desirable programs, or media gatekeepers who have the power to tell stories that move an issue higher on the social agenda.

Here is a brief summary of some general techniques in social marketing, with comments on their applicability to a PPD context:

Authority—Using a figure of authority, knowledge or trustworthiness to provide a more believable message. Suggested for early stages of a campaign.

Peer Influence—often, target groups are most easily influenced by members of their own age, race, party, or cultural or socio-economic background because they can identify with them. Appropriate to the tailoring and delivery of messages to different target groups.

Benefits—messages designed to appeal to rational thought and decision-making, showing how behavior serves an audience’s self-interest. Suggested for higher-level target groups such as senior businesspeople and politicians, etc.

Celebrity—using celebrities to promote ideas based on the notion that target groups identify with certain public personalities and thus will want to adopt the endorsed behavior. Suggested for lower-level target groups such as small enterprises or skeptical sections of the general public.

Consistency—after committing to a given position, people are more likely to behave in a manner consistent with that position – once behavior has been changed it is often appropriate to have people wear buttons or use bumper stickers to support a cause. Suggested strategy for later stages of the campaign.

Social Validation—people are more likely to act or subscribe to a belief when they see that others are doing so. This bandwagon effect is worth exploiting once stakeholders have started to come on board.

Moral Messages—appeals that are directed to the target group’s sense of what is right and wrong. This appeal is appropriate to the issue of using PPD to promote transparency.

Testimonial—messages based upon the assumption that audiences will respond to those who have changed behaviors and are benefiting from this change. Suggested for later stages in the campaign.

C.6.D.2. Make clear the benefits of participation, as people will already see the costs

Each target audience will clearly perceive the costs to themselves of becoming involved in PPD – time, effort, and, in the case of public sector actors and other champions, a potential risk to credibility. It is important that communication materials make clear to each set of participants the potential benefits they can expect from involvement.

C.6.D.3. Map communication strategies to stakeholder analysis

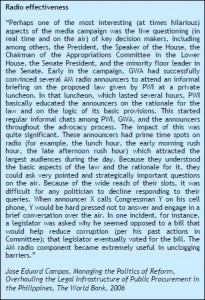

Different stakeholders require different communication strategies depending on their attitude to PPD. The stakeholder analysis described in the introductory diagnostic tool will help identify how to reach out to different groups of stakeholders.

A communications assessment analysis may also be necessary to draw up more specific strategies. This can take the form of interviews with opinion leaders, focus groups and surveys. The aim is to identify opponents who are not unmovable, allies who may waver in their support, and stakeholders who are involved but uncommitted – reaching these three groups requires effort. The diagram maps the effort needed from a communications strategy at each point of the spectrum.

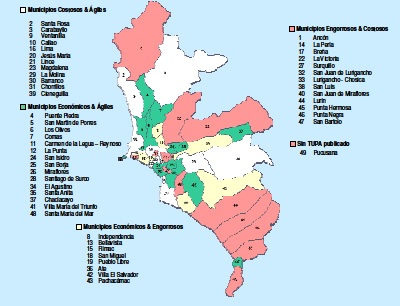

Citizen-friendly benchmarking: Case study from PeruCuidadarnos al Dia is a civil society organization in Peru which seeks to create the political will for business climate reform. The key to creating public demand for reform is “citizen-friendly benchmarking” – gathering facts and making them available through the media in an immediately accessible way. CAD’s mantra is: “If your grandmother couldn’t understand it, it’s worthless.”

An especially successful technique is the use of color-coded maps. This map shows the results of a benchmarking exercise in Lima, comparing the time and cost of registering a new business in each municipality. Every resident can see at a glance which are the best- and worst-performing municipalities, giving locally elected politicians no place to hide.

Full case study from Cuidadarnos al Dia available in the Country Cases section.