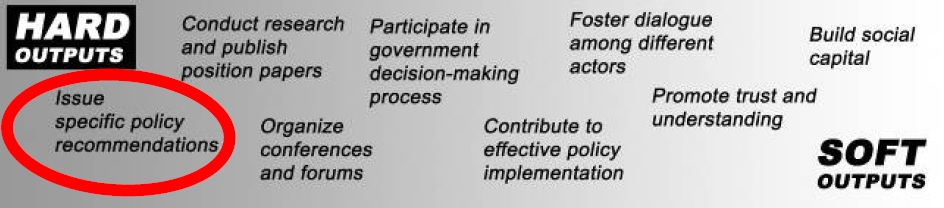

The issue: Dialogue is not an end in itself – it is a means to outputs. Choosing the right outputs to aim for can be critical to a dialogue’s chances of success.

development outcomes.

- Analytical outputs can include identification and analysis of business roadblocks, agreement on private sector development objectives, and private sector assessment of government service delivery.

- Recommendations can address policy or legal reform issues, identification of development opportunities in priority regions, zones or sectors, or definition of action plans.

- Structure and process outputs can include a formalized structure for private sector dialogue with government, periodic conferences and meetings, ongoing monitoring of public-private dialogue outputs and outcomes, and a media program to disseminate information.

- Outputs should be measurable, time bound, visible, tangible and linked to indicators.

C.5.1. Types of intended outputs

Intended outputs can be more or less ambitious, ranging in scope from holding conferences and producing discussion papers to enabling legislative programs. Proposing quantifiable measures for success will depend of the type of output selected. Some possibilities are:

• The holding of an annual forum, as happens in Vietnam.

• The target of “50 economic reforms in 150 days” of Bosnia’s Bulldozer, each reform being a specific regulatory change.

• To “double the level of innovation by having at least 20 percent of all enterprises introducing some new product, process or service in the previous two years”, as adopted by the Shannon region of Ireland as part of the EU’s Risk Innovation Strategies.5

• An aim for improvement in a country’s ranking in indices – such as the World Bank’s Doing Business indicators, the World Economic Forum’s Growth Competitiveness index, or the OECD’s Human Development Index – which is among the objectives adopted by Nigeria Economic Summit Group and Better Business Initiative.

| Output type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Analytical outputs | “Think pieces” that survey the investment climate territory and set recommendations in context. These include policy papers, position papers, reviews and assessments. All need to be informed by evidence-based research. |

| Specific Reform Recommendations | Specific recommendations for reforms to policies, laws or regulations, including suggested texts for draft new laws or amendments when appropriate. |

| Structure and process outputs | Conferences, meetings, functional monitoring and information dissemination programs. While these outputs are ultimately futile if they do not lead to any other kind of output, it can nonetheless be worth setting targets for them. |

| “Soft” outputs | Increases in trust, understanding and cooperation between stakeholders; building of social capital. |

A focus on policy reforms – which can be defined as any change in a legislative or administrative system that will impact the end users of that system – is a common thread of many PPD mechanisms. This covers a broad range of meanings: passing a new law, a change in an internal procedure in a local administration, amendments to an article in a law, a ministerial instruction, a change in the way licenses or permits are handled, a different tax rate, a harmonization of procedures, and so forth.

Japan’s deliberation councils show what can be achieved when consultation accumulates legitimacy by being seen to work well over a period of time – policies approved by the councils are implemented almost routinely, whereas any proposal emanating from the Ministry of Trade and Industry that has not passed through a deliberation council has little chance of passing parliament.6 Several approaches can be considered to implement actions based on the problems identified.

C.5.1.1. Immediate commitment to resolve discrete problems

Some problems can be resolved immediately, when a government leader or head of an institution acknowledges the existence of a problem and when there is an easy and quick way to resolve it by, for example, altering internal procedures or preparing information for businesses. In such cases, the secretariat should document the commitment and follow up on whether it is implemented. Section C.5.4 and C.5.5 below provide mechanisms that can be followed to achieve such goal.

C.5.1.2. Action plan as a comprehensive tool to coordinate related activities in the short to medium term

For medium-term solutions (which can be undertaken within six months and up to two years) the preparation and adoption by the government of an action plan to address the problems identified is helpful. An action plan is a documentation of the discussions between the government and the business community and is a commitment by the government to the business community that implementation will be carried out. The action plan thus serves as a basis for business to monitor implementation of measures. It indicates priorities and allocates responsibilities including:

- what problems need to be solved,

- what reforms will be undertaken to solve them;

- who will be responsible for implementing the reforms;

- when they should be completed; and

- how they should be assessed.

Experience suggests that an action plan is not the most appropriate instrument for resolving longterm issues, like education reform or reduction of corruption. This is because the action plan is most successful when it is based on discrete activities that can be undertaken and completed, and whose impact can be monitored and evaluated.

C.5.1.3. White Paper/Roadmaps for major adjustments or long-term goals

Finally, some broad problems that are identified to be the root causes of certain administrative barriers can only be resolved in the medium- to long-term. This is because there needs to be a conceptual evaluation of the problems, which are often complex and multi-faceted, and thus can generate various options for their resolution. In addition, political support for the issues must be generated. But a prerequisite to political support is the preparation of information, its dissemination, consideration by the interested parties, and receipt and inclusion of their comments. Examples include a study on pre-court appeals mechanisms, broader judicial reform, a white paper on a new system of cadastral valuation in determining the real estate tax, broader tax reform, customs reform, land reform, or other broad, major reforms requiring major policy reforms rather than regulatory/procedural reforms. In terms of content, the common thread for all these types of studies are a presentation of general principles as well as what specific activities should follow. These “roadmaps” are described in more detail below in section C.5.8.

C.5.2. Aim for hard, quantifiable benefits – soft benefits will come

naturally

“Soft” benefits – increased trust and understanding – tend to arise as by-products from striving for outputs that are more easily quantifiable. Some possibilities for quantifying outputs: holding of meetings; publication of reports; recommendations made; reforms passed. Look at the M&E chapter for more ideas on how to quantify soft benefits.

C.5.3. Focus the dialogue on specific policy issues, possibly starting with “low-hanging fruits”

The initiative needs to be focused on either specific issues or specific types of reform at first. The risk of falling far from the initial goals is high as the group tries to tackle too many sectors and too many types of reforms.

In Turkey, the YOIIK initiative initially focused on investment-related issues before expanding to other areas, dismantling working groups once the issues they dealt with were resolved, and creating new ones to tackle new issues. This ensured that energy was concentrated where it was needed, and where most results could be achieved in the short term. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bulldozer initiative tackled many sectors of the economy, but focused on a specific type of regulation: it limited its work to small regulatory changes that could have a quick impact and that only demanded amendments into laws or regulations, thus avoiding lengthy political battles that the work on legislative overhaul or on more structural reforms would have brought.

An obvious but effective strategy is to start by picking the “low-hanging fruit” – reforms that are relatively easily achievable because the need for them is generally recognized and they are unlikely to meet serious resistance. This builds initial momentum – but care must be taken not to let this lead to unrealistic expectations of continued easy success.

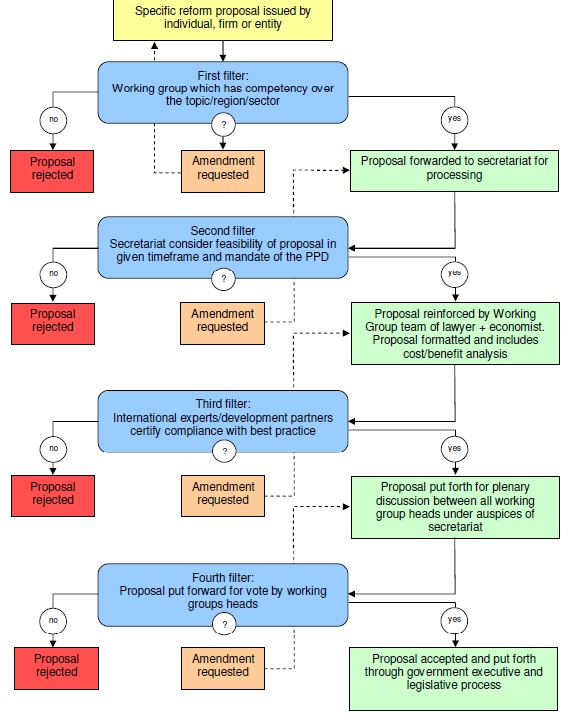

C.5.4. Creating and processing proposals

As discussed below in the chapter on outreach and communications, it is helpful to have an outreach program to elicit reform suggestions from the grassroots. These reform suggestions need to be expertly assessed, filtered, and transformed into standard format recommendations for reform. This implies a need for a specialized technical committee of lawyers and economists, who will need to evaluate reform proposals, develop legal solutions, and perform a cost-benefit analysis. The filtering process is necessary to ensure that reforms which reach the stage of being proposed to government must show a benefit to the economy as a whole, and not serve the narrow interests of one group. A selection of approved reform suggestions can then be put to a vote to determine which should be submitted to government.

Section C.5.6. below maps in detail a possible filtering process.

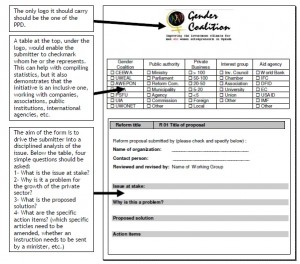

C.5.5. Use standard forms to capture reform proposals

A standard form enables stakeholders to submit ideas in a transparent and fair way. Reform proposals to be considered by a PPD should be captured by a standard form and submitted either directly in working group meetings, in public information meetings or even by mail or e-mail.

Once formatted through such a form, a reform proposal is a few pages long and indicates the specific laws/regulations/actions to amend/take place in each relevant jurisdiction. It can include the text of existing articles, shown side by side with the new text recommended for adoption.

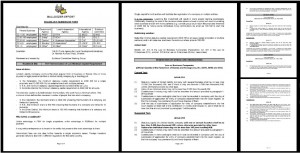

The figure below contains a reform proposal submitted during the Bulldozer initiative in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In just four pages, the reform deals with complex issues – minimum capital requirement, minimum value of shares, and harmonization of regulations in different jurisdictions. Yet the clear and simple format allows a legislator to understand the intent of the proposal and the reasoning behind its submission, and to directly assess the validity of the proposed amendments.

C.5.6. Invite reform suggestions and filter them for quality control

To seen by all actors as legitimate, recommendations to government that emerge from a PPD must not only be clear, well-researched, and compellingly presented. They also must pass through a transparent filtering process. The failure of the Private Sector Roundtable in Ghana was partially attributed to the fact that its recommendations were “overly vague and, due to poor background research, failed to include analysis of such vital matters as cost implications”, and furthermore were not accompanied by a realistic timetable for implementation.8 See section C.12. 5. to learn how donors can be involved in the filtering process.

C.5.7. Tracking the selection process of reform proposals generated by PPD is crucial

Tracking the progress of reform proposals from initial suggestions through to concrete

recommendations for reform – if this is an intended output of the PPD – provides useful insights into the effectiveness of the suggestion filtering process. It also serves to promote transparency and build the legitimacy of final proposals by demonstrating how they came to be adopted. The figure below details a typical filtering process.

See the annex C1 for sample standardized issue submission form.

C.5.8. Roadblocks vs. roadmaps

Although policy reform recommendations should be specific, that doesn’t mean they can’t be presented on more than one level. It is a good idea to create separate “product lines.”

On one hand, specific reform proposals to be acted upon in the short tem by the government can be produced by the PPD.

On the other hand, as a way to create less direct pressure and to ensure sustainability of the effort over the long run, working groups can aim to produce more general research pieces taking a birds-eye view of the business landscape and describing the broader context for required reforms, such as economic strategy documents.

It is therefore recommend that a PPD develop a set number of targeted proposals (called, for example, “Business Roadblocks”), together with a smaller number of high quality, longer and research-based economic policy papers (e.g. “Business Roadmaps”). The Roadblocks promise concrete outcomes and instant gratification, while the Roadmaps build credibility by putting the Roadblocks in context.