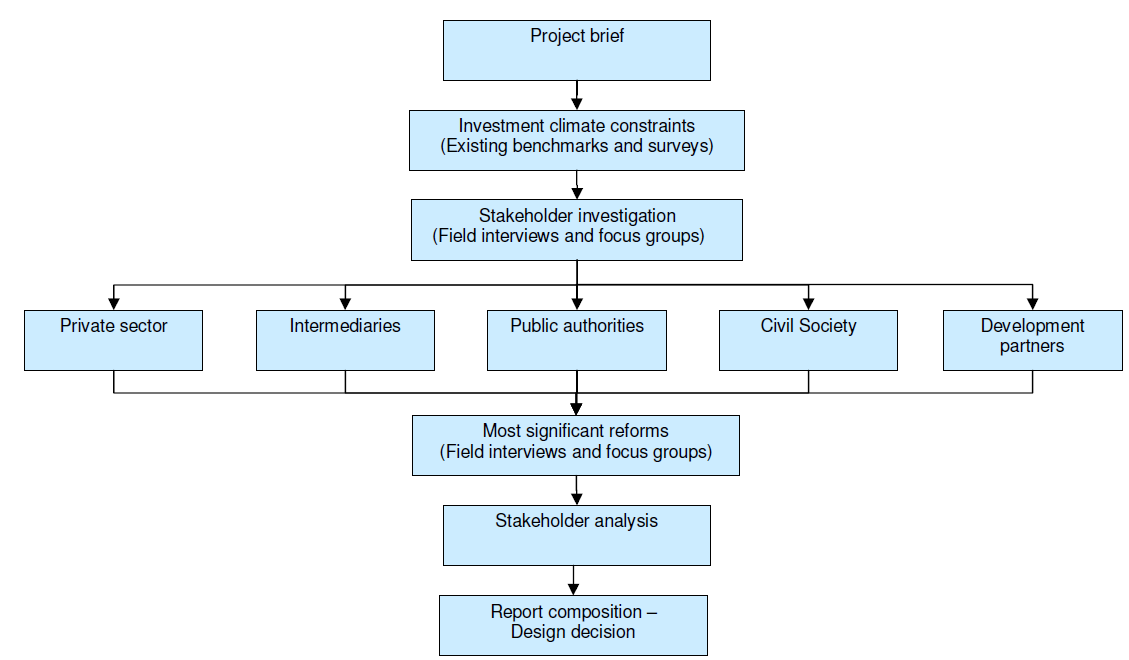

The above figure represents the different steps to be taken during the PPD diagnostic. Each step is detailed in the sections below.

In term of time management, it is estimated that the completion of the diagnostic project takes 14 days:

Writing the project brief – 1 day

Investment climate constraints (desk study) – 3 days

Stakeholder investigation (field interviews) – 3 days

Most significant reform (field interviews) – Integrated into the above.

Stakeholder analysis (field and/or desk) – 2 days

Report writing – 5 days

Total: 14 days.

B.2.1. Project brief

The project brief sets the terms of reference (ToR) for the project. These are the key elements it needs to define:

- The rationale for the exercise

- The geographic area where it will take place and public sector jurisdictions it will cover

- Mention of any relevant previous exercises or knowledge

- The types of outputs desired from the diagnostic: only a report, or also recommendations?

- Names of people who will manage the project.

- Budget and time allocation for the project.

- Project plan, including the sequences of activities through which the project will go and details of each activity

- Monitoring and evaluation indicators for the project.

- Target completion date.

B.2.2. Investment climate constraints

This phase of the mapping tool relies on desk research of existing surveys and benchmarks, such as the World Bank’s Doing Business reports and Investment Climate Surveys. Specific sources of information should be collected from the closest field office if available, and from practitioners who have knowledge about the studied location.

The aim here is to build up an overall understanding of the nature of private sector activity in the country or region under consideration, with specific emphasis on constraints to private sector development.

This enables the project team to understand the terrain and have a preparatory framework for

understanding the responses received during the stakeholder investigation phase.

Key questions to consider at this stage:

- What are the main constraints on the private sector?

- What are key existing and potential sectors for the economy?

- Have priorities been identified in a Country Assistance Strategy or Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper?

- Are there institutions dealing specifically with PSD who could contribute more knowledge in

this desk research phase? - How important is foreign investment compared to home-grown enterprises?

- Do state-owned industries have a prominent role?

- What is the balance between large and small enterprises?

- Have larger companies shown interest in developing local supply chains?

- Is there a strong regional concentration of private sector activity, both in general and around specific sectors?

- How large is the informal sector?

- How important is the export market?

This series of questions is aimed at identifying where the bottlenecks to business investment lie. If task managers want to fit this investigation within an overarching structure, we advise them to use a tool such as the Policy Framework for Investment (PFI), which was developed by a task force of 60 OECD and non-OECD economies and in partnership with the World Bank Group. Such tool is useful to ensure a comprehensive and coherent diagnostic. The World Bank’s Doing Business reports and Investment Climate Surveys actually offer indicators to use in response to the PFI checklist questions.

The PFI brings together ten sets of questions covering the policy domains having the strongest

impact on the investment environment and represents a comprehensive and integrated approach to

diagnosing and implementing good policy practices for mobilizing private investment that supports development (see box). The PFI can be downloaded at: www.oecd.org/daf/investment/development

The 10 policy areas of the PFI are a useful guide to diagnose business environment

constraints.

- Investment policy: The quality of investment policies directly influences the decisions of all

investors, be they small or large, domestic or foreign. Transparency, property protection and nondiscrimination are investment policy principles that underpin efforts to create a sound investment environment for all. - Investment promotion and facilitation: Investment promotion and facilitation measures, including incentives, can be effective instruments to attract investment provided they aim to correct for market failures and are developed in a way that can leverage the strong points of a country’s investment environment.

- Trade Policy: Policies relating to trade in goods and services can support more and better quality investment by expanding opportunities to reap scale economies and by facilitating integration into global supply chains, boosting productivity and rates of return on investment.

- Competition policy: Competition policy favors innovation and contributes to conditions conducive to new investment. Sound competition policy also helps to transmit the wider benefits of investment to society.

- Tax Policy: To fulfill their functions, all governments require taxation revenue. However, the level of the tax burden and the design of tax policy, including how it is administered, directly influence business costs and returns on investment. Sound tax policy enables governments to achieve public policy objectives while also supporting a favorable investment environment.

- Corporate Governance: The degree to which corporations observe basic principles of sound corporate governance is a determinant of investment decisions, influencing the confidence of investors, the cost of capital, the overall functioning of financial markets and ultimately the development of more sustainable sources of financing.

- Policies for promoting responsible business conduct: Public policies promoting recognized concepts and principles for responsible business conduct, such as those recommended in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, help attract investments that contribute to sustainable development. Such policies include: providing an enabling environment which clearly defines respective roles of government and business; promoting dialogue on norms for business conduct; supporting private initiatives for responsible business conduct; and participating in international cooperation in support of responsible business conduct.

- Human resource development: Human resource development is a prerequisite needed to identify and to seize investment opportunities, yet many countries under-invest in human resource development due in part to a range of market failures. Policies that develop and

maintain a skilled, adaptable and healthy population, and ensure the full and productive

deployment of human resources, thus support a favourable investment environment. - Infrastructure and financial sector development: Sound infrastructure development policies ensure scarce resources are channelled to the most promising projects and address bottlenecks limiting private investment. Effective financial sector policies facilitate enterprises and entrepreneurs to realise their investment ideas within a stable environment.

- Public governance: Regulatory quality and public sector integrity are two dimensions of public governance that critically matter for the confidence and decisions of all investors and for reaping the development benefits of investment. While there is no single model for good public governance, there are commonly accepted standards of public governance to assist governments in assuming their roles effectively.

To complement the general diagnostic on the business environment, the desk research phase should also identify a significant recent reform to serve as the basis of the “most significant reform” exercise (see below section B.2.4.).

While it is important to collect and digest reports, the best source of knowledge is often phone, email, or face-to-face conversations with practitioners who have worked in the country or location where PPD is being diagnosed. It is a wise investment of time to find such practitioners, as their insight is likely to be invaluable in preparing for the field interviews.

B.2.3. Stakeholder investigation

The aim of the stakeholder investigation phase is to map the perceptions of potential participants and stakeholders in PPD. These include the private sector, intermediary organizations, the public sector and civil society.

The methodology for this phase includes interviews and focus groups. The sections below outline

what the reports should tell us about each of the five types of stakeholder.

Annex B includes sample questionnaires that can be adapted for interviews and focus groups with each type of stakeholder. These are also available as Word documents on www.publicprivatedialogue.org/tools. The questions are intended as a starting point, to elicit

responses that will be helpful in compiling the diagnostic report (also in the annexes). They

should not be treated as exhaustive – questions can be added, deleted and adapted according to local context and needs.

B.2.3.1. Private sector

A representative sample of businesspeople should be interviewed. What constitutes a representative sample should be informed by the above analysis of the composition of the private sector, and by initial findings as to which companies have been active policy advocates or not.

It is important to include various groups that play a significant role in different sectors and industries of the market, from small-scale informal entrepreneurs to foreign multinational corporations.

Key questions to be answered:

- What are perceived to be the main investment climate constraints?

- Does the private sector interact directly with the government or with government officials? At what levels does this interaction take place? (Ministerial, departmental, civil servants, mayors, low-level bureaucrats, etc).

- Have businesspeople attempted to get their concerns heard by the government? Have there been attempts to organize? With what degree of success?

- What is the general attitude of entrepreneurs towards government? Is it characterized by a feeling of trust or is there frustration? Do politicians and businesspeople frequent the same social circles or do they rarely interact?

- How much time do businesspeople spend dealing with government agencies? Are dealings with government officials fair and transparent or do they tend to involve informal payments?

- To what extent do businesspeople keep track of laws and regulations? Is there a sense of predictability and stability of policies? What are the mechanisms by which they stay informed about policy and regulatory changes?

- What is the legal capacity of the private sector? Is it easy to get advice on abiding by laws and regulations?

- Do businesspeople typically belong to a representative membership organization? Do they feel they are well served by them?

- To what extent do small entrepreneurs believe that the interests of large and small enterprises diverge and coincide?

- Are there dynamic individual business leaders who command widespread respect and could act as figureheads in the PPD process and champions for the private sector? Who are they?

B.2.3.2. Intermediary organizations – e.g. business membership organizations (BMOs), Chambers of Commerce, etc

Organizations that serve as intermediaries for the private sector to represent its concerns to the public sector come in many forms. They may or may not exist in any given region – and if they do exist, they may be more or less effective at representing their members and providing services. The most common types are summarized in the table.

Characteristics and Functions of Different Types of BMOs2

| BMO Type | Defining Factor | Typical Functions and Services |

|---|---|---|

| Trade/industry Associations | Occupation/Industry | Arbitration, quota allocation,industry standards setting, lobbying, quality upgrading |

| SME associations | Size of firm | Entrepreneurship training and consulting, finance schemes, group services |

| Women’s associations | Gender | Entrepreneurship training,microfinance, gender-specific advocacy |

| Employers’ associations | Labor relations | Interest representation vis-àvis unions, professional information, and training |

| Confederations | Apex bodies | High-level advocacy, general business information, research, coordination of member associations |

| Bi-national associations | Transnationality | Trade promotion, trade fairs, matchmaking |

| Chambers | Geographic region | Delegated government functions, arbitration courts, basic information services, matchmaking, local economic development |

Key questions that the diagnostic report must answer about intermediaries:

- Do private sector representative organizations exist? What kind?

- Are they vibrant and inclusive or moribund or captured by narrow interest groups? Which are

the most effective organizations? Which have the most dormant potential? - How effective are intermediary organizations at representing their members at national and

local level? - What kind of services do they offer to their members? (Training? Services on behalf of public authorities? Information on laws and regulations?)

- What kind of information dissemination services do they provide? Do they organize regular

meetings? Do they gather information on the binding constraints faced by their members? - Do they genuinely represent the interests of SMEs?

- Do they have any important recent accomplishments?

- What is the importance of other kinds of intermediary between government and the private

sector, such as lawyers and notaries? - Are there institutional linkages between business membership organizations and government

agencies or public bodies?

The report should include a table that summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of different

intermediary organizations, such as this example:

| Intermediary | Mandate | Membership Type and Size | Strengths and Accomplishments | Weaknesses | Contact Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturers Information | Represent manufacturers in policy discussions. Provide training services, advice on setting up companies and mediation with unions. | Voluntary. 720 businesses are members, representing 32,000 employees. | Legal department is well regarded and arbitration service commands respect. Some successful input into recent labor regulations bill. | Narrow membership based around the automotive industry and in one city. Foreign investors are ineligible for membership. | |

| Chamber of Commerce | “Organize, represent and promote the country’s private sector interests.” | Compulsory. All businesses with more than 10 employees must join. | Existing membership gives it the potential to reach all businesses. Legal mandate gives it close links with government, which could be capitalized on. | Widely seen by its members as corrupt, ineffective and not democratic. Compulsory membership fee is resented. |

B.2.3.3. Public sector

The attitude of the public sector can make or break public-private dialogue. Public sectors are rarely homogenous in their willingness or capacity to engage in dialogue – there will often be wide differences between different levels of authority, agencies, departments, and regions. The mapping tool needs to identify the pockets of capability and enthusiasm.

- What is the level of capacity of technical staff at each level of the public sector?

- What are attitudes of politicians and civil servants towards the private sector?

- Are there mandatory requirements for government bodies to engage with the private sector?

Which ones, at what level, and at which stage in the process of enacting a legislation or

regulation? - Have the public authorities issued safeguards to prevent cronyism, trained public sector

officials in handling relationship with the private sector, or communicated internally about

public-private relationships? - Are there any government departments regarded as especially favorable or inimical to private sector concerns? Which are they?

- Are there any individuals who can act as public sector champions for reform and who are not

perceived as politically divisive figures? Who are they? - What is the extent of decentralization of decision making?

- To what extents do local layers of government have responsibility for implementing decisions taken at national level?

- How effectively do layers of government work together?

| Department or program | Jurisdiction and audience | Strengths and accomplishments | weaknesses | Contact Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| President’s office | Advises president on appointing ministers, structure of national government, new policy initiatives. | Personal access to president. High concentration of enthusiasm for private sector development and technocratic ability among foreign educated staffers. |

Regarded as out of touch with the public. Often have difficulty in practice in getting their initiatives accepted by other departments. | |

| Ministry of Trade and Industry | Regulates industry and represents government in international trade talks. | Strong negotiators. Minister is one of the most powerful figures in government. | Many civil servants have bureaucratic mindset and take a confrontational approach to private sector. |

B.2.3.4. Perceptions of civil society

Dialogue between the public and private sectors does not take place in a vacuum. The attitude of civil society towards private sector input into policymaking is a critical success factor. The mapping tool must therefore diagnose the views of civil society towards the private sector and potential dialogue.

Civil society includes:

- labor union representatives;

- non-governmental organizations (NGOs);

- academia; and

- media

Questions to be answered in the report about civil society:

- Are small-scale entrepreneurs generally perceived as contributing positively to society or as untrustworthy and parasitic?

- Are larger and foreign-owned businesses viewed as contributing positively to society or as

untrustworthy and parasitic? - Is the government generally perceived as overly hostile to the private sector, overly

accommodating of the private sector as a whole, or beholden to vested interests within the

private sector? - Are international donor agencies, who could act as sponsors and champions for dialogue,

perceived as part of the country’s problem or the solution? - Are there leading think tanks or academics that produce research-based recommendations on

private sector development? - What are the media outlets that produce radio or TV programming or written content about

the economy? What are their distribution, reach and limitations? - Who are the leading media figures who have an influence on different types of population

(youth, workers, seniors, etc.)? - Which NGOs deliver economic aid, and what types?

- What are the main trade unions? Which sectors do they represent? Are they perceived as overprotecting workers at the cost of economic growth, or are they perceived as the last line of defense against ultra-liberalization?

- Is there a lot of transferability of competencies between the civil society and the government? Or is it rare to see a leading academic taking a government position?

Some of the answers may be captured in a table of similar format as in the previous and next round of questions.

B.2.3.5. Perceptions of development partners

In countries where the international development donor community, or development partners, have a strong presence, their attitudes towards PPD can also help to determine its chances of making an impact.

The task manager should conduct interviews with representatives of the major development partners present in a country and compile a matrix mapping their perceptions of dialogue and potential for contributing.

| Development partner | Significance of presence in country | Potential for contributing to dialogue | Contact Information | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFID | Small field office, mostly concentrating on governance and civil society. | Private sector development is not a focus of DFID’s presence here. But broadly favorable to PPD in principle. | Could be willing to consider seed funds and technical assistance for aspects of dialogue that specifically promote good governance and civil society. | |

| World Bank | Has had major role in development of economic policies over the last two decades. | Strongly favors private sector development. Favor idea of PPD but have established views about the best ways to promote PSD. | In a strong position to provide expert policy advice. Too close an involvement in decision making could risk dominating the views of local stakeholders. |

B.2.4. Most significant reform

As mentioned above, the desk research stage should have identified a recent reform impacting the private sector, which can serve as the basis for this phase of the mapping exercise. There is no objective way to judge which recent reform is most significant, but this does not matter – if there are several contenders, any one or two reform efforts will suffice.

The aim here is to look at a recent reform and see what happened in practice with regard to the dialogue process and the success of the law. Which interactions between the public and private sectors facilitated the process, and which created interferences that resulted in the reform failing to be adopted as intended? The report should identify gaps in the process, which can join the stakeholder investigation to feed into the analysis of the state and potential of PPD.

- To what extent was private sector input sought, received and acted upon during (a) the

diagnosis, (b) the solution design, (c) the implementation and (d) the monitoring and

evaluation phases of the reform process? - Was private sector input based on sound research reflecting the interests of the private sector as a whole, or did it reflect vested interests?

- How did the government react to private sector input, if any?

- What was the contribution of civil society to the debate, including the media?

Through these questions, the task manager should aim to identify specific performance and

opportunity gaps, and put them in relation with examples of good practice dialogue that may have taken place in the country or location in question, if any.

Performance gaps serve to indicate how a system of public-private interaction that should have been working did not work to its full performance, and why.

Opportunity gaps are potential new interaction systems that were missed during the reform process and could have been beneficial to its outcome.

B.2.5. Final report template

Before the report is drafted, those who will participate in the dialogue should obviously have the opportunity to discuss the design. This will build good habits and increase buy-in for the design and prepare the field for disseminating the report findings.

The final report should always include an analysis of:

- investment climate constraints;

- private sector concerns and capacity for dialogue;

- intermediary organizations;

- attitude of civil society towards the private sector;

- public sector attitudes and capacity for dialogue; and

- role of donors in supporting the dialogue process.

The report should include the tables outlined above dealing with the strengths and weaknesses of intermediary organizations and government agencies. Other sectors should be addressed briefly and clearly.

B.2.5.1. Stakeholder analysis

If the report also aims to provide recommendations about establishing or improving public private dialogue, it should also contain a stakeholder analysis.

Doing a stakeholder analysis helps task managers identify:

- individuals and government agencies or departments that are the most willing and capable of engaging in the dialogue process;

- government agencies or departments most necessary for dialogue to succeed and their state of capacity and political will;

- How pockets of capability and enthusiasm within the public sector can be leveraged to bring key agencies and departments into the process;

- any vested interests within the private sector that have undue influence over government decision-making;

- Any stakeholders who are likely to oppose the idea of dialogue, and the reasons; and

- existing intermediary organizations that can be strengthened, and if not, whether it is necessary to create new structures to fill a gap.

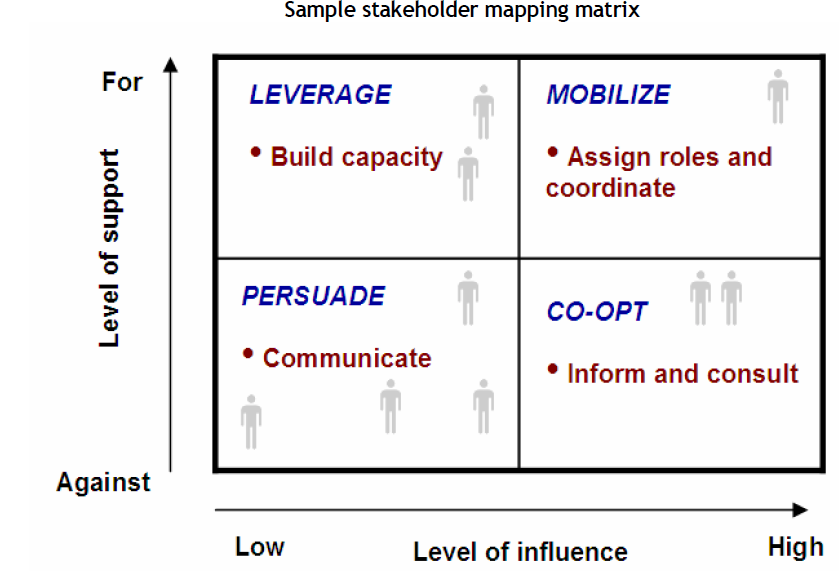

Stakeholder analysis should inform strategies for proceeding with PPD. The stakeholder analysis matrix, below, provides a useful framework for identifying which stakeholders need to be approached with which kind of strategy.

Stakeholders who favor the idea of PPD and have a high degree of influence can be brought on board at an early stage of developing dialogue by assigning roles to them and coordinating their input. Stakeholders who favor dialogue but are less influential can be targeted for capacity building.

Where opposition to the idea of dialogue is found, special efforts can be made to co-opt the most influential opponents by informing them about the purposes of dialogue and consulting them about how the design of dialogue mechanisms can make the process more acceptable to them.

Stakeholder analysis is highly dependent on context, and depending on the analysis of the different players, task managers will need to customize a stakeholder management approach responding to the specific challenges of the situation.

B.2.5.2. Recommendations

Diagnostic reports can be for analysis purposes only, leaving stakeholders to fill in the details of how dialogue should proceed. Sometimes, however, the project brief will call for a specific set of recommendation on a draft design for a proposed dialogue mechanism. In these cases, such a design should aim at including the following:

- A draft mission statement.

- Roles of stakeholders, including principles for selection of participants and optimal

participation of donors. - Functions of a secretariat – who should organize meetings, circulate information, organize

external resources, etc. - Proposals for organizing working groups, e.g. by issues, sectors, locality.

- Agenda of initial key issues, based on consultations, respecting both public and private

perspectives, and proposed mechanisms for introducing new agenda items in the future. - Operating guidelines for dialogue – how often will stakeholders meet, the process for reaching consensus, feedback mechanisms, degree of openness, relationship with government and

parliament, etc. - Nature of outputs – what kind of outputs the dialogue should aim to produce, e.g. policy

recommendations, policy papers, etc. See section C II, below, for further ideas. - Support services that may be required, such as research on issues;

- Communications and outreach strategies, identifying target groups and suggesting methods;

- Organizations that would benefit from capacity-building to enhance dialogue.

To design these recommendations, a strategic planning workshop with the future PPD leaders or participants can be more than helpful. It enables all sides to discuss mission, goals, strategy, action plan, etc.

The next section of this handbook will serve to inform the recommendations that could be made.